Discussions about a shortage of qualified mental health professionals are becoming more frequent in Switzerland. Concerns are growing about increasingly difficult access to psychiatric care. This is reflected in the longer waiting times than in most other medical specialties. A 2024 survey of specialists shows that adults wait an average of 41 days from the initial contact to the consultation, while children and adolescents wait even longer—around 56 days. By comparison, waiting times in other outpatient medical fields are much shorter: about 9 days in general surgery and 7 days in oncology. The only outpatient fields with longer wait times are endocrinology and diabetology, at around 71 days. So, are these long waiting times the result of a shrinking supply of psychiatric services?

International Top Rankings in Psychiatrist Density

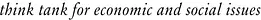

While there were 2,017 practicing psychiatrists across Switzerland in 2000, this number had risen to 4,672 by 2022—an increase of about 132%. During the same period, the Swiss population grew by roughly 1.8 million. Despite the population growth, the psychiatrist density increased from 28 to 53 per 100,000 inhabitants, nearly doubling over the past two decades. It’s important to note that these figures refer exclusively to psychiatrists; psychotherapists are not included.

Psychiatrist density in Switzerland is very high by international standards (see Chart 1). It is three times the OECD average and significantly higher than in neighboring countries—about twice as high as in Germany and France, and nearly three times that of Italy. Growth has also been remarkable: between 2000 and 2022, the psychiatrist density in Switzerland increased by 2.2% annually, compared to 1.0% in Germany, 0.3% in Italy, and 0.2% in France.

Although the OECD data count individuals regardless of employment level, a 2015 study commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) also calculated the number of psychiatrists in full-time equivalents (FTEs): in Switzerland, this amounted to 40 FTEs per 100,000 inhabitants. Even so, the density remains very high compared to neighboring countries.

Significant Cantonal Differences

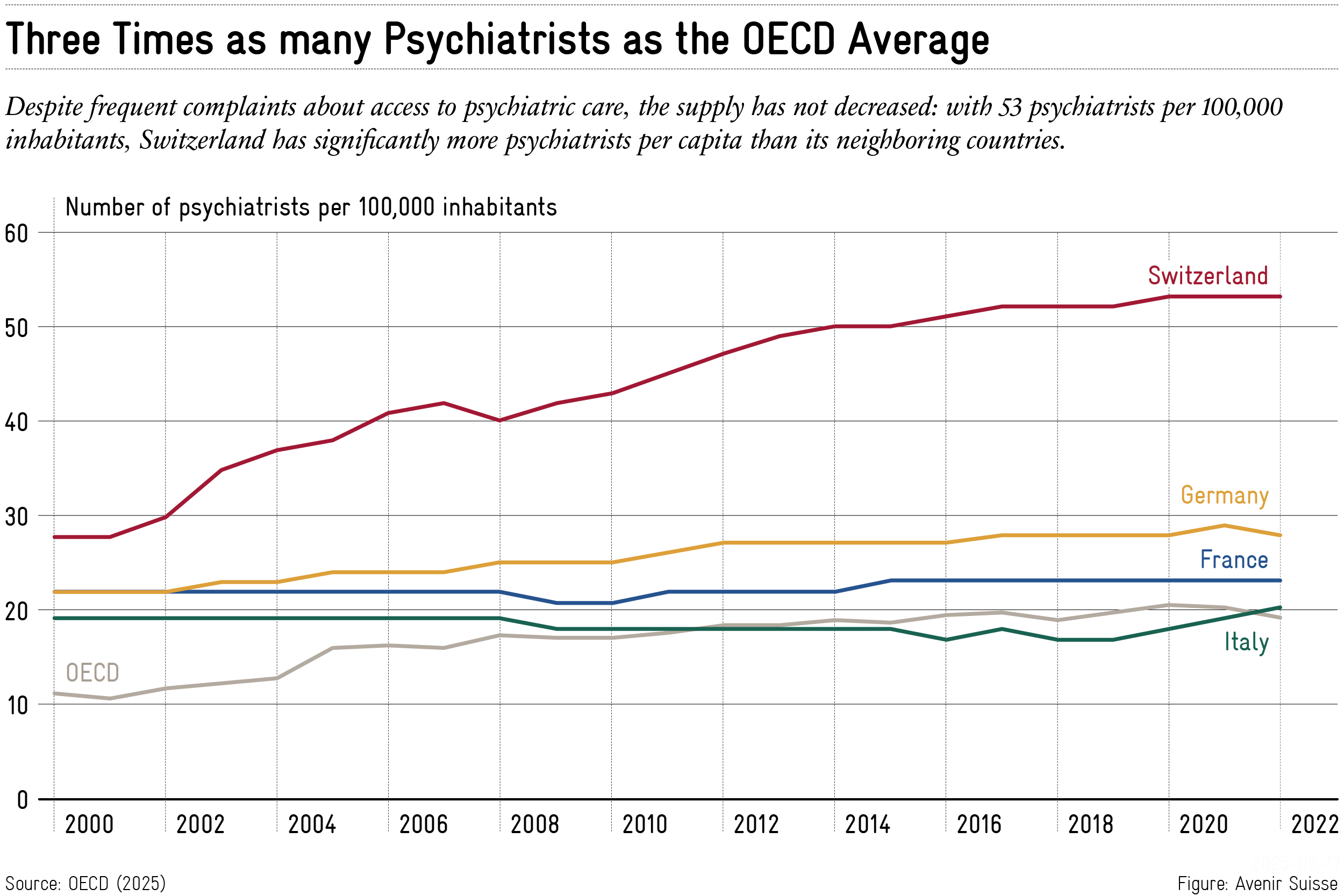

The high national psychiatrist density conceals large disparities between cantons. While the canton of Obwalden has only 10 psychiatrists per 100,000 inhabitants, the canton of Geneva has 99, and Basel-Stadt even 123. There is no clear divide between the French- and German-speaking regions (“Röstigraben”); rather, these differences seem to reflect the degree of urbanization in each canton (see Chart 2).

In the case of smaller cantons, it is important to consider that they are sometimes served by neighboring urban centers. For example, it is conceivable that people from the cantons of Obwalden, Nidwalden, or Uri receive treatment in Lucerne. Especially for mental health treatments, it is likely that some patients seek anonymity outside their place of residence or prefer locations close to their workplace.

Even in cantons with low psychiatrist density, the figures often remain above the OECD average. For example, while the density in the cantons of Valais and Graubünden is significantly below the Swiss average, it still exceeds that of Germany and France.

Better Understanding the Difficult Access

The frequently criticized access to psychiatrists cannot be explained on a national level by a generally declining supply. The data clearly show that psychiatrist density in Switzerland has increased—and is very high by international standards. However, the regional picture is more nuanced—with some cantons having comparatively limited availability.

So what explains the difficult access? The likely cause is rising demand. Various factors are commonly cited: the influence of social media, increasing social isolation, and the destigmatization of mental illnesses and therapy. However, these trends also exist in our neighboring countries—which still have significantly lower psychiatrist densities than Switzerland.

It is therefore worth investigating whether the demand for psychiatric support is growing disproportionately in Switzerland—or whether structural shortcomings in the healthcare system are preventing the existing resources from being used efficiently. A better understanding of these specific characteristics in Switzerland is necessary before expanding services nationwide. The goal must be to make psychiatric help available where it is genuinely lacking.