Over half a century ago, in 1972, we established the three-pillar system of retirement provision in our constitution. In 2025, we’ll celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Federal Act on Occupational Retirement, Survivors’ and Disability Pension Plans, the BVG/LPP. When it was introduced, the Swiss pension model received a lot of attention and was presented as a role model by the World Bank. But has the concept proven its worth in practice and on a political level?

Robust and differentiated

The Swiss pension system is structured to provide a differentiated response to the needs of society. Its components are a universal OASI (old-age and survivors’ insurance) pension scheme covering all citizens (not just the working population), a company-specific occupational pension (OP) fund, and an individual, voluntary pillar 3a retirement savings option.

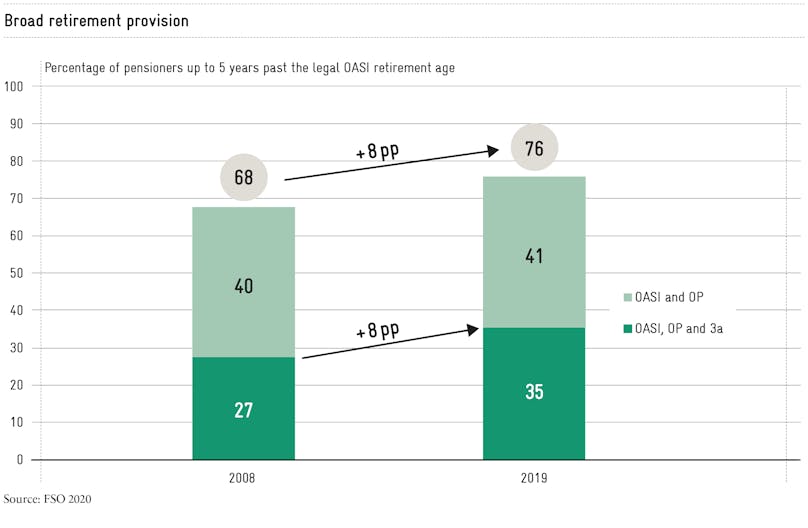

More and more people are benefiting from this broad-based system of old-age provision. In 2008, two-thirds of new pensioners received a pension from the first and second pillar; in 2019, three out of four did so. Pillar 3a, which was introduced in 1987, is increasingly being used as well. In 2021, every other new pensioner, including early retirees, was retiring with this type of pension solution.

The three-pillar concept also enables risks to be diversified. The funding of the OASI (government) pension depends primarily on the domestic economy and demographics, whereas the second and third pillars give access to the global capital market, with its associated opportunities and risks. This diversification makes the system robust. It has been weakened but has always been sufficiently funded, even during the Covid-19 pandemic or the market collapses following the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

Fit for reform, albeit slowly

However, a positive overall performance in recent decades shouldn’t blind us to the need for action. Society and the work environment have changed considerably, and adjustments have been necessary in all pillars.

The three-pillar approach increases the system’s openness to reform. (vug.)

It’s also the three-pillar concept that makes the system more reform-friendly. Blockades of the kind that occurred in France this spring, for example, where adjustments to the pension plans of certain groups immobilized the entire country, do not occur in Switzerland. That said, the last reform of the first pillar took almost a quarter of a century. The issue was the alignment of the women’s retirement age with that of men; it was controversial and caused a major political stir.

During this time, however, it was possible to continuously update the decentralized second pillar. Boards of trustees, equally composed of employer and employee representatives, have adapted the technical parameters to the demographics and the working world. Today, 91 percent of pension funds have a conversion rate below 6.8 percent. The coordination deduction, which weakens pension provision for part-time employees, has been made flexible or completely abolished by 88 percent of pension funds.

In the third pillar, the rigid restriction that contributions may only be paid in a given year will hopefully be eased soon thanks to the Ettlin motion adopted by Parliament in 2020.

Reform is an ongoing process

Despite additional funding from the TRAF reform in 2019 (CHF 2 billion per year via percentages of pay) and the OASI 21 reform in 2023 (up to CHF 1.5 billion per year via value-added tax), sustainable financing of the OASI system is not yet assured. According to the Federal Social Insurance Office, there will be a pay-as-you-go deficit of CHF 3.4 billion in 2033. The upcoming initiative “for a 13th OASI pension” would further raise OASI expenses by 8 percent and increase the need for funding. With or without the initiative, a reform is inevitable.

Additionally, last February’s ruling by the European Court of Human Rights requires an adjustment of widows’ and widowers’ pensions. Under the current regulations, widowers are significantly worse off than widows. As a result, women receive 98 percent of the benefits. Widows with no children are also paid life-long pensions. Eliminating this unequal treatment shouldn’t just bring men’s benefit levels into line with women’s. What’s needed is a modern, gender-neutral solution that supports fathers and mothers with young children and that is reduced as the age of the children increases.

Reforms are pending in the second pillar as well. People will vote on BVG 21 in 2024. As mentioned, most pension funds have come up with their own responses. The reform would improve the situation for the remaining 10-15 percent of pension funds. However, it comes at a high price. To relieve the working population of a redistribution of CHF 400 million per year to pensioners, which is contrary to the system, working people will have to bear twice the costs, CHF 800 million per year, for the transitional generation.

Inflation: an old friend is back

Inflation is back after an absence of almost two decades. But this is nothing new for retirement pensions. At the end of the highly inflationary 1970s, the OASI introduced partially automatic indexation of pensions in the form of the so-called mixed index. Wage increases and consumer prices each account for 50 percent in the calculation. This led to rising pensions even in years without inflation, for example after the fixed exchange rate with the euro was abolished. In 2023, the minimum monthly OASI pension is 16 percent higher than twenty years ago, while consumer prices, including the record year 2022, have only risen by 11 percent.

The lack of such automatic adjustments of pensions to inflation in occupational pension plans is often criticized. But the criticism is only partly justified. When the BVG was introduced, it was assumed that pension funds would be able to generate a nominal minimum return of 4 percent to finance pensions. Inflation of 2 to 3 percent and a real return on federal bonds of around 1.5 percent were factored in. The reason for not indexing was that senior citizens tend to spend less as they get older and can therefore bear a moderate devaluation of their pensions. So inflation was not ignored when the second pillar was introduced. What was perhaps underestimated, however, was people’s financial needs in old age.

As of 2005, pension funds have also been allowed ‒ to the extent that their finances permit ‒ to adjust current pensions to price developments. Today, this would only be justifiable on the grounds of intergenerational fairness if the assets of active employees were also protected from inflation, i.e., if the interest on their assets were higher than inflation. Anything else would be a cold expropriation of the active population in favor of pensioners.

This article was originally published in German in “Finanz und Wirtschaft”.