In the previous article of our “Migration Insights” , we focused on the makeup of today’s resident population — in other words, the stock. This article turns to the flow of migration. The question here is not how many people live in Switzerland, but how migration has been shaping the country year after year — and who, has been arriving in Switzerland.

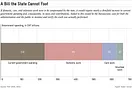

Final figures for 2025 are not yet available. Still, net immigration of foreign nationals — defined as the balance of arrivals and departures within the permanent resident population — is expected once again to exceed 70,000. That would be in line with the average of the past two decades, though below the exceptionally high levels recorded in the most recent years. In 2024, net immigration stood at around 90,000.

The peak came in 2023, when net immigration reached 148,000. That unusually high figure is largely explained by the war in Ukraine: About one third of net immigration that year consisted of Ukrainians who had arrived in 2022 and, after a year of residence, were statistically counted as part of Switzerland’s permanent resident population.

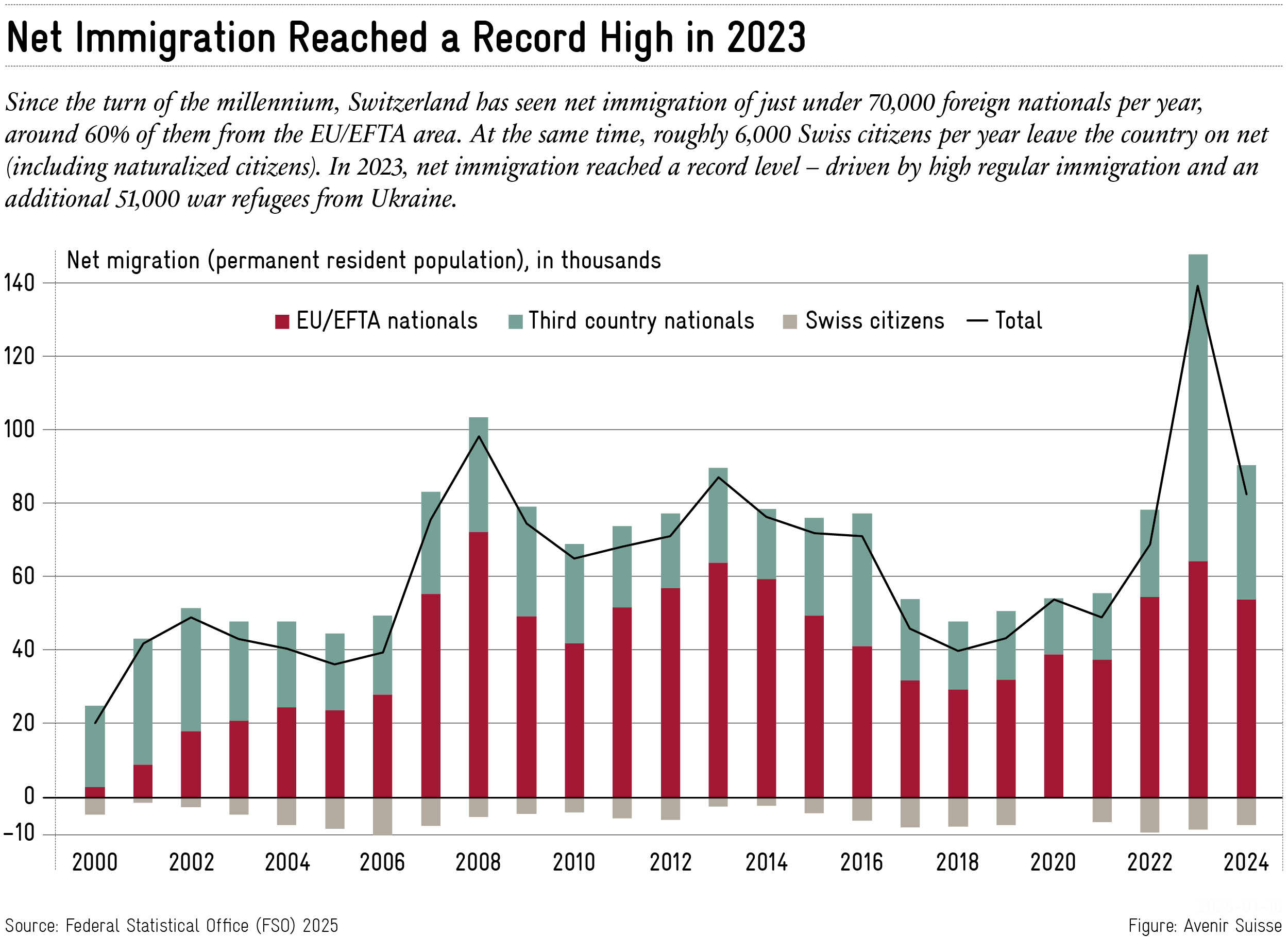

Since the turn of the millennium, net immigration of foreign nationals has averaged about 68,000 people per year. In cumulative terms, that amounts to roughly 1.7 million people by the end of 2024. Three fifths (60%) of that net inflow came from the EU/EFTA area. Looking only at the period since 2007 — the year full freedom of movement with the European Union took effect — the average annual net inflow rises to 77,000, with 64%coming from the EU/EFTA countries.

While immigration from European countries tends to track the business cycle, the same cannot be said for immigration from non-European third countries. Access to the Swiss labor market for third-country nationals is tightly restricted; family reunification therefore plays a significantly larger role.

About one third of net immigration since 2000 can be traced to Switzerland’s three largest neighboring countries. Above all, the number of immigrants from Germany has risen sharply since the late 1990s. In 2008, Germans accounted for a net inflow of 34,000 people — nearly half of total immigration from EU countries. After a temporary decline, they have once again become the largest group among new arrivals.

The composition of immigration is constantly shifting, often reflecting economic conditions in countries of origin. Compared with neighboring states and Southern Europe, countries in Eastern Europe played a much smaller role for a long time. With the gradual opening of the labor market following the EU’s eastward expansion, immigration from these countries — particularly Poland, Romania and Hungary — did increase, though it stabilized relatively quickly.

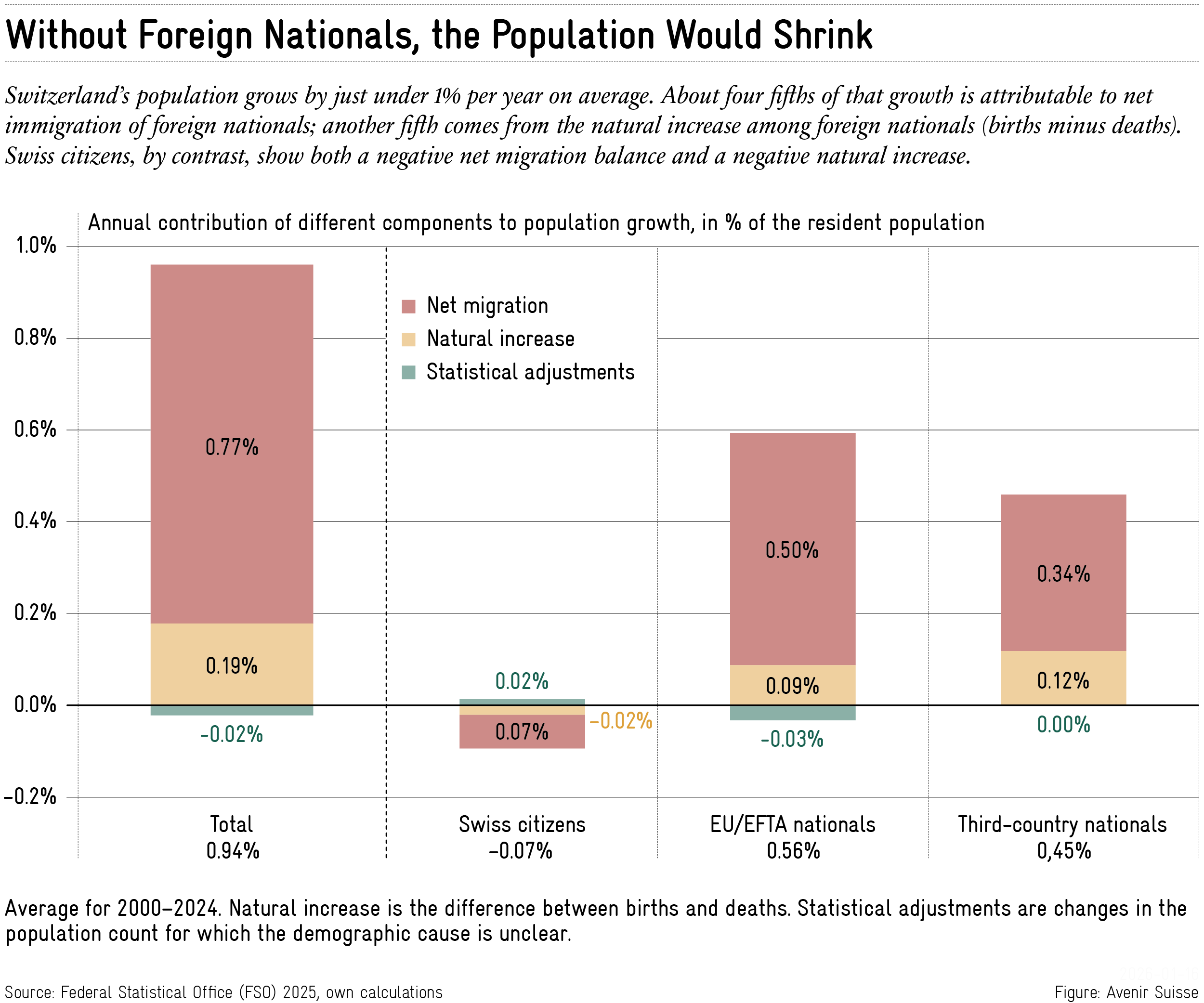

The high levels of immigration in recent years have contributed to a marked rise in Switzerland’s resident population. Since 2000, the population has grown by 1.9 million people, surpassing 9 million by the end of 2024. Average annual population growth came to 0.94%, or roughly 75,500 people a year. About four fifths of that increase is attributable to the international net migration balance; the remaining one fifth comes from natural increase — that is, births minus deaths.

Swiss citizens, by contrast, have posted a negative migration balance: Each year, more Swiss leave the country than return. Meanwhile, more Swiss nationals now die than are born. As a result, overall population growth is effectively driven entirely by the foreign population. The only reason the number of Swiss citizens has still inched upward over time is naturalization.

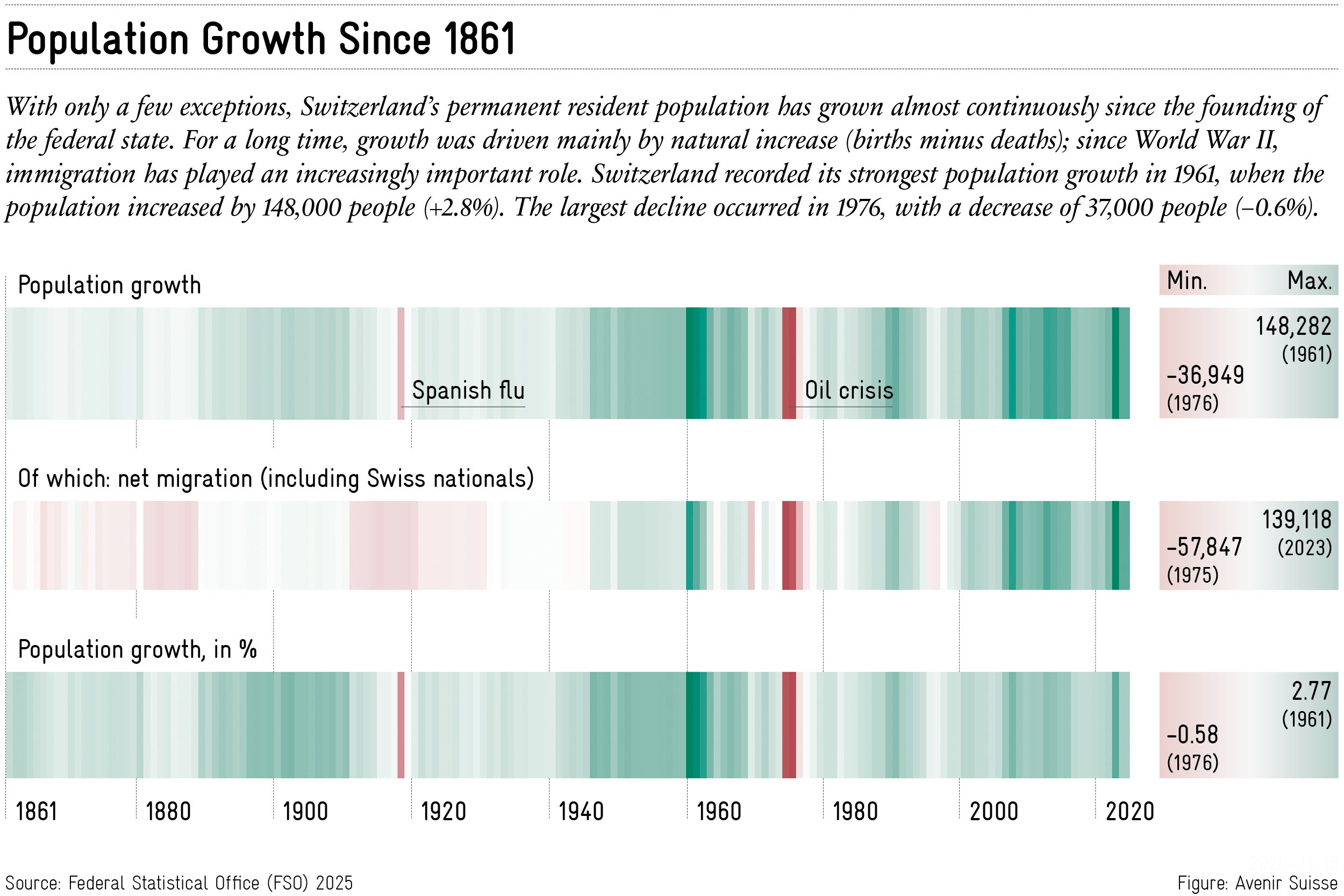

In absolute terms, today’s persistently high migration figures are historically unusual. Switzerland has experienced waves of strong immigration before — most notably in the early 1960s, when net immigration reached 101,000 in 1961. But in those years, peaks were regularly followed by periods of much lower net inflows. That volatility has diminished. The elevated level has become more sustained.

When viewed in the context of total population growth, however, today’s numbers appear somewhat less extraordinary. That is because natural increase — the birth surplus — used to be the decisive driver for a long stretch of Switzerland’s modern history. In 1961, for example, Switzerland recorded not only a large immigration gain but also a birth surplus of 48,000, making it the record year for Swiss population growth. Where two engines once powered demographic expansion — births and migration — net migration today is increasingly the country’s dominant force.

Migration Insights

Migration is shaping Switzerland—politically, economically, and socially. Hardly any other topic is debated as intensely and emotionally. With its blog series on migration, Avenir Suisse sheds light on the many facets of immigration to Switzerland. We provide data and facts to foster a better understanding of Switzerland as a country of immigration.