Just like similarly non-EU Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland, Switzerland is an associate member of the Schengen border free travel agreement.In June 2005, 54.6 percent of Swiss voters backed associating with the linked Schengen/Dublin agreements, in spite of repeated doubts. “The Action Committee against Schengen Accession”, for example, argued: “Schengen brings open borders, more criminals, more undeclared workers, lower wages, more unemployed Swiss, foreign law and finally EU accession” (voting booklet, page 11).

800 million border crossings per year

More than a decade later, it’s clear those fears have not materialized. Great Britain and Ireland are not Schengen members, and retain their own border controls. However, the Brexit negotiations have demonstrated that, even for islands, hard borders can be politically controversial.

Switzerland, by contrast, surrounded by four EU member states and an EEA country, is at the heart of Europe, playing a central role in the north-south movement of people and goods. Border regions around Geneva, Ticino and Basel are among the most dynamic economic areas of the country, with thousands of foreign workers.

In 2018, Switzerland had 312,325 cross-border commuters. Not only the Swiss economy, but also Swiss citizens, benefited from such unhindered mobility. Figures from the Federal Statistical Office show that in 2015, 805.5 million people crossed the Swiss border in vehicles and by rail. That equates to 91,952 people an hour (excluding air traffic). Of course, commuters or shopping tourists inflate the data by their frequent entries and exits. But the figure illustrates the possible consequences of systematic border checks on persons.

Applying the Schengen agreement affects both Swiss multinationals, which are often active in border areas, and Swiss mountain cantons, which gain from increased tourism from third countries like India, China, Thailand, Russia and the Gulf States.

According to the State Secretariat for Migration, 479,465 Schengen visas and 67,404 national visas were issued in 2017. The high demand for Schengen visas lies in the fact that tourists want to travel to other European countries too. If Switzerland were not in Schengen, such visitors would have to apply for a separate Swiss visa when travelling to Europe. That would form an additional disincentive on top of the already sky high Swiss franc.

Cross-border investigations

At first glance, operating an open border poses risks to internal security. The Schengen Information System (SIS) has taken this into account. Thanks to its Schengen deal, Switzerland has full access to this database, launched in 1995 and holding more than 75 million entries.

Without Schengen, a criminal being pursued by police in one Schengen country could easily enter Switzerland, because Swiss authorities might be unaware he is wanted internationally. Given the increasingly cross-border nature of criminal networks, the SIS offers significant benefits. Thanks to Schengen, more than 4,000 people have been arrested over a period of 10 years, while the number of search hits has doubled compared to the pre-Schengen era. Fedpol figures for 2017 show a search hit every 30 minutes, the bulk stemming from Illegal migration.

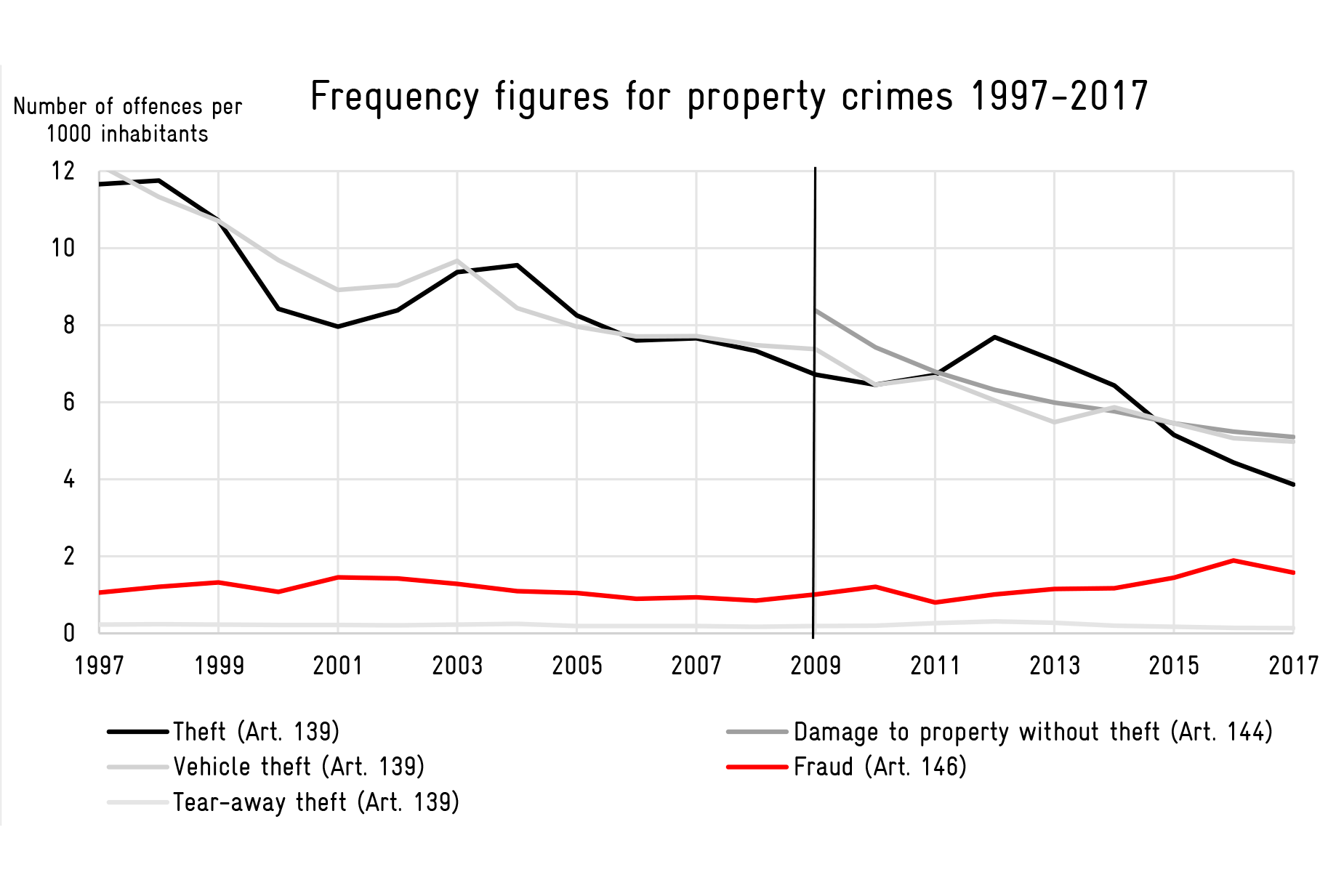

The statistics on police-registered offences show falling numbers since Schengen came onto force at the end of 2008. But it would be misleading to draw a causal link here. The growing number of search hits should in theory lead to more registered offences. It can, however, be assumed that, thanks to international networking, police work has become more effective and thus has a deterrent effect.

While that could be related to the declining crime statistics, what can be said for sure is that the feared rise in criminality due to open borders has not happened. Data for burglary, vehicle theft and tear-away theft or robbery, threats and bodily injury, show no spike in so-called “criminal tourism”.

Fewer asylum applications and costs thanks to Dublin

Discussion about Schengen often overlooks the linked Dublin pact. But the latter has also brought clear advantages to landlocked Switzerland, surrounded by countries appealing to asylum seekers. Under the Dublin rules, only one state is responsible for procedures for asylum seekers. During the asylum process, fingerprints are taken and recorded in the Eurodac database to ensure a person makes only one application.

Without Dublin, Switzerland would have no access to Eurodac and no recourse to the Dublin mechanism. Asylum seekers with a negative decision from Italy, for example, would be free to submit a second application here, which the Swiss authorities would be obliged to examine. This could draw in additional asylum seekers, apart from creating much more red tape.

Why we should implement Schengen/Dublin correctly

Schengen is not only important for the full mobility of citizens, it also central to cross-border trade, tourism and asylum. It does not threaten Swiss sovereignty. Rather, it helps the Swiss police do their job, thanks to improved information. Criminal organizations often work and operate transnationally – including in Switzerland. So the correct implementation of Schengen is central to guaranteeing internal security and citizens’ individual freedom.

More information about SIS is available here:

Schengen Visa Info

Visa Guide