For many Swiss households, the new year brings higher electricity prices. Compared to 2023, electricity costs for a typical household (H4) will rise over 18 percent on average in 2024. The increase compared to 2021 – when costs began to rise quickly – will be 57 percent. And this, despite the fact that market prices have fallen considerably. Even futures, meaning the current price fixings for electricity supply in one month or even two years’ time, have halved compared to the previous year and this is probably due to the fall in gas prices. By generating electricity from gas in Europe, gas prices have a lot of influence on the price of electricity.

Households and SMEs will not benefit from market developments for the time being. A positive impact on customers in the basic supply due to falling prices is not expected until 2025. The reason behind this is that around 70percent of the approximately 630 electricity supply companies do not have their own power plants. They purchase the electricity demand of their customers on the market. This is usually done in units over several months to smooth out price fluctuations. The high prices, particularly in 2022, will therefore continue to have an impact for some time.

No escape from the electricity monopoly

Divided in two, the electricity market in Switzerland makes it impossible for small consumers (as opposed to large consumers) to change supplier. However, the differences are substantial: according to Elcom, the prices for one kilowatt hour in the basic supply range from 10.22 to 57.48 centimes in 2024. For households and commercial enterprises, this could lead to a considerable strain on the budget.

Political attempts to grant consumers a free choice of their electricity provider have been around since the 1990s, but unsuccessful so far (for example recently during the parliamentary discussion on the consolidation legislation). Basic supply is considered an ideal from a political point of view, intended to protect households from the vagaries of the market. However, this year’s price increases clearly show that this is not the case.

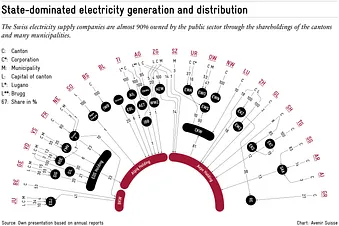

Ultimately, basic supply does not protect customers. If anything, it protects energy supply companies, of which almost 90 percent are owned by the public sector, i.e. the cantons and municipalities. Only around 8 percent are in private Swiss ownership, 2 percent belong to foreign investors. The illustration shows the holdings in substantial energy supply companies of the 26 cantons and larger municipalities. Additionally, cantons and municipalities hold shares in the three largest electricity companies in Switzerland, both directly and indirectly through their energy supply companies: BKW and Alpiq are predominately publicly owned, while Axpo is fully owned by the public sector.

Download the chart as pdf

Changes since the last data collection

This is not the first time that Avenir Suisse draws attention to the major interdependencies in the electricity industry. We already highlighted those back in 2007 and 2015. Although the ownership structure has not changed fundamentally, there have been some notable changes in recent years:

- In 2016, EKZ acquired almost 30 percent of Repower during a capital increase. As the major shareholders at the time, Axpo and the canton of Graubünden, did not follow suit, EKZ became principal shareholder. The canton of Zurich holds shares in Axpo both via the EKZ and directly. It therefore owns over a third of Repower.

- In 2016, BKW sold its share in Romande Energie among others to the city of Lausanne.

- In 2019, the French energy supplier Electricité de France (EdF) sold half of its shares in Alpiq to EOS Holding (owned by the cantons of French-speaking Switzerland) and half to Primeo Energie. A year later, the shares were acquired by a Swiss energy infrastructure fund.

- In 2020, the canton of Solothurn ended its long-standing investment in Alpiq and sold its block of shares to IBB Holding AG, which in turn is owned solely by the city of Brugg.

- In 2022, Axpo sold its minority share of just under 13 percent in Repower to the previous shareholders EKZ and the canton of Graubünden, among others.

The relations illustrated here are by no means complete and are in fact more complex. There are further connections through shareholdings in the grid operator Swissgrid and in partner companies. Nevertheless, the most important relations are highlighted.

In times of high prices, state-owned electricity companies are tempted by profits. For 2023, they are likely to amount to several billion francs for the largest energy supply companies. A big part of the profits will go to the state. In the event of market prices falling below production costs, losses are occurring which was the case several years ago. A discussion arose as to whether the owners – i.e. the cantons and municipalities or their taxpayers – would have to step in in an emergency.

Several reasons in favor of a reform

The present structure and ownership situation of the electricity supply industry are unsatisfactory for several reasons:

- The role of the state as regulator and owner is questionable. This can be seen, for example, in cantonal laws that demand an explicit profit transfer from their cantonal energy companies. The term “shadow tax” is obvious. Public owners of companies with monopoly positions do not treat their customers better per se than private investors in companies that are in competition.

- The original idea behind cantonal and municipal ownership was most likely to finance the development of infrastructure but also to be able to intervene directly at any time. However, this idea is becoming less important, as energy policy is largely shaped at national or even European level. Added to this is the fact that Switzerland is a price taker, meaning that electricity prices on the market are set abroad.

- The current substantial profits could be reversed in the future and taxpayers would have to step in. Discussions in the past (see rescue package) show that this would most likely happen through the federal government and not through cantonal owners. It would be a lack of solidarity with those cantons that have not benefited from profits in the past at all or not enough. Furthermore, the federal government has no democratically legitimized mandate to rescue ailing energy supply companies – as with banks. Once again, the emergency law would probably be applied.

- Many energy supply companies are expanding into economic sectors where private players are active already. There is no market failure, therefore state intervention is not necessary. One example is private electrical installation companies. They are taken over by state-owned energy supply companies. It is often unclear whether the money for the acquisition comes from business with customers in the free or captive market. Honi soit qui mal y pense. Such expansion strategies are not democratically legitimized. They are openly rejected by the remaining private electrical installation companies, as the large state-owned competitor not only has access to greater financial resources, but also generally enjoys an implicit state guarantee.

- Complete market liberalization would lead to consolidation among the approximately 630 energy supply companies. This would also speed up professionalization, which is essential in view of the increasingly complex regulatory framework. The outdated model of the municipal employee, who is also responsible for the municipal energy supply company on a 20 percent workload, no longer has a future.

The historical justification of public ownership of the energy supply companies in terms of public service may refer to security of supply, but it did not save us from the threat of energy shortages a year ago. It is time to take the first step towards complete market liberalization to create more competition and, as a second step, to consider the privatization of the energy supply companies.

More information on this topic can be found in the publication “Energy Policy under Strain”