Power shortages in Switzerland? Over here we’re only familiar with large-scale power outages lasting several days from the movies or foreign countries. But this could change. In an extreme scenario, Swiss households would be left in the dark for up to twenty days at a time – in winter, of all times, when people are particularly dependent on light and heat. Without electricity, it wouldn’t just be LED lights that failed, but also thousands of heat pumps installed with public funds.

It’s no coincidence that the Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP) considers a power shortage to be the greatest risk for Switzerland – even more so than a pandemic. According to this analysis, only an armed conflict would be more expensive in terms of the extent of the damage it caused. The threat of a shortage of electricity might have been accentuated by the Russian war of aggression, but the situation was already serious even before that. In the fall of 2021, for example, the Federal Council called on around 30,000 companies to prepare for future power shortages.

Large Government Footprint

The threat of energy shortages is due not least to a lack of government foresight. The state exerts a powerful influence on the Swiss electricity market. On the supply side this is due to the high level of public-sector ownership of dominant companies such as Axpo, Alpiq, BKW, CKW, Repower, and EOS, whose direct or indirect shareholders are in most cases local public energy suppliers, cantons, and municipalities.

On the demand side, under the current law only larger electricity consumers (with an annual consumption of over 100,000 kWh) have a free choice of supplier; Swiss private households and small businesses have been awaiting the promised liberalization since 2014. This means that 99% of consumers in Switzerland are forced to obtain their electricity from their local monopoly.

Hydropower Blocked by the “Alpine Opec”

It’s not just the opportunity to assure security of supply that we’re missing, despite lavish subsidies, but also the energy transition. Compared with other European countries, Switzerland’s trump cards are neither solar nor wind energy, but hydropower. However, investments in dams apparently aren’t very attractive from an economic point of view. One reason for this is the water rates that for over a hundred years now have been charged to those using water to produce power. This charge accounts for up to one third of the costs of generating electricity.

But there has been no fundamental reform to make hydropower more competitive. Instead, the legal basis has been extended in response to pressure from the mountain cantons, and the charges have even been steadily increased. Around 550 million Swiss francs a year in water rates now flow to the local cantons and municipalities – regardless of whether electricity is actually being produced or the price for which it’s being sold on the market. Swiss energy policy is being held hostage by regional interests. Of course, the so-called Alpine Opec has also made sure that these revenues aren’t taken account of when determining the amounts redistributed under the national financial equalization scheme – in other words, local authorities pretend to be poorer than they really are to receive more funds.

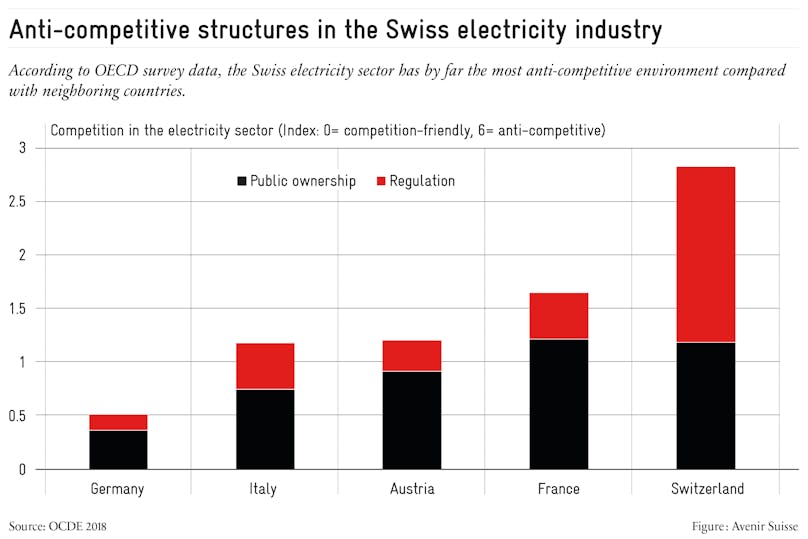

Competition-unfriendly Framework

Security of supply? Energy transition? Both seem to be secondary considerations when it comes to collecting money for your own region. But that’s not all: the profitability of hydropower is further diminished by regulations on residual flow. This reduces the amount of water that can be put through the turbines – but doesn’t alter the water rates. The Swiss electricity market operates within an anti-competitive framework; it’s not very dynamic, and innovations have a hard time gaining acceptance. Yet now more than ever we need more ideas to meet the challenges ahead of us.

The Status Quo Ends in Darkness

The likelihood of electricity shortages is growing because of the absence of an electricity agreement with the EU. Energy policy has been part of the collateral damage resulting from Switzerland’s unilateral decision to drop negotiations on the institutional framework agreement.

Switzerland has been excluded from most technical coordination and expert bodies. Coordination with European partners has therefore become increasingly difficult, even though Switzerland, with all its cross-border lines, is physically the best-integrated country in Europe. The only thing that’s lacking is the political will to create closer contractual ties.

As a result, unplanned cross-border electricity flows are already burdening the Swiss power grid. If, for example, Germany and France trade electricity, part of it flows through Switzerland. This is because the physically determined path of the electricity does not follow the theoretical route agreed in the contract. These unexpected power flows require immediate intervention by the transmission grid operator Swissgrid. Without these interventions, the grid in Switzerland would no longer be stable, resulting in blackouts. Whether it will be possible to maintain grid stability at all times in the future is an open question; demand is continuously increasing. In the short term, therefore, the objective should be to reduce such unplanned electricity flows through Switzerland by means of better arrangements and technical agreements.

In the medium term – by the end of 2025 – Switzerland will definitely become a third country from the EU’s perspective. By then, our neighboring countries will have reserve at least 70% of their border capacities for electricity exchange with other EU countries. They can only comply with this by limiting transmission capacity to Switzerland. In total, more than three times less could be imported and more than four times less exported than today. Our market access will thus be severely restricted, and grid security will be at risk.

Challenging to-do List

Switzerland has a challenging to-do list on the energy front:

Firstly, domestic electricity generation must be stepped up as quickly as possible. Increasing Switzerland’s degree of self-sufficiency is economically costly but necessary, especially if it’s to cope with the winter months. This will mean prioritizing the expansion of new capacity over other goals.

Secondly, the market needs to be more dynamic and innovative. This should include the gradual privatization of electricity companies – spread over a period of, say, ten years. In addition, the market must be liberalized completely to allow new players with new solutions to enter.

Thirdly, Switzerland needs to improve its relations with the EU. From the electricity industry’s point of view, the short-term goal should be to conclude a technical agreement to stabilize our grid and not apply the border capacity clause to Switzerland. In the medium term, signing a balanced electricity agreement should be on the agenda to enable equal participation in the EU’s internal market.

Switzerland needs its “man on the moon moment” in terms of electricity policy. Security of supply and innovation must be ensured “not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.” (President John F. Kennedy at Rice University, September 12, 1962).