French train drivers, London Underground workers, Glasgow rubbish collectors; all represent groups of employees of state-owned businesses performing essential public services under increasing threat from technological and social change.

Few more so than the post office. Digitalization and the rise of the internet have cut deeply into traditional letter writing and postal marketing. Fast, easy, and virtually cost free, email now overshadows conventional letters as a means of communication. Even data heavy documents can be transmitted instantly over broadband internet.

Dense networks of post boxes and postal outlets are under pressure. Who needs a post box on every corner when the letter post has plummeted? And what is the use of hundreds of post office counters when so much is done online? Deregulation has exacerbated matters, opening traditional services to new, often more efficient, private sector entrants, most recently Covid-19 has raised the stakes by turning even more potential customers online.

Swiss exceptionalism

Switzerland is by no means alone in facing such challenges. But, compared with European neighbors that have, to greater or lesser degrees, already restructured, the country’s enduring tenet of “service public” has allowed the authorities here to avoid the most brutal cuts. While public telephone kiosks may have vanished as fast as elsewhere, the country maintains one of the densest networks of post boxes, requiring personal collection five or six days a week.

Across Europe, cutting costs and axing unprofitable services has been the most common response to structure change. But these are not the only options. Some European postal systems have expanded into new, more lucrative, areas, to cross subsidize their public service mandate. Germany’s Deutsche Post, for example, long a stock market quoted company, has extended into parcels and logistics. Britain’s Royal Mail, a more recent stock market arrival, is following suit.

The third option – price rises – has also been practiced widely. But it has its limits. Lifting postal costs too sharply immediately hits volumes. And higher prices for stamps, while unpopular everywhere, prompt a particularly strong backlash in Switzerland, where the concept of “service public” is so entrenched.

What is to be done?

What, then, is the solution for such beleaguered operators? Avenir Suisse’s Samuel Rutz in a recent blog examined the alternatives for Switzerland’s postal service. The company, he notes, has explored all three avenues, cutting where practicable, expanding where opportunities arise and attempting to raise prices where possible.

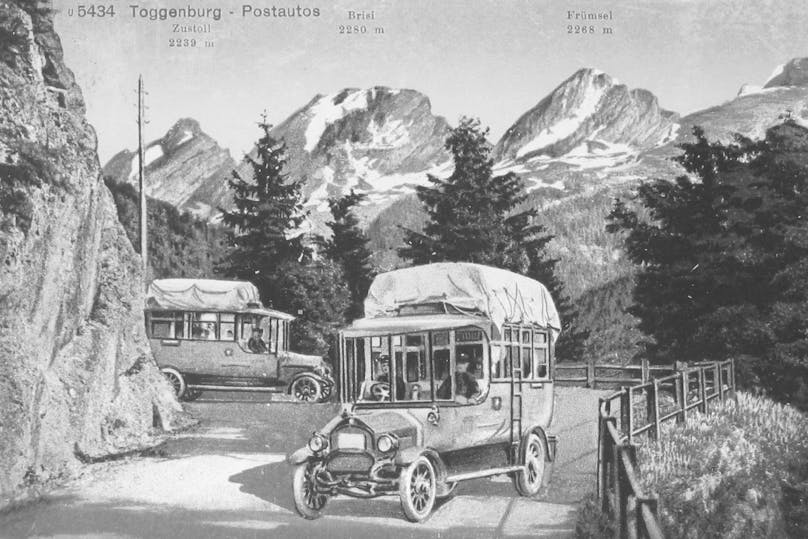

An old postcard with Post Office vehicles from 1920. (ETH Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv)

But the particular status of the Swiss post office – and “service public” in general – presents a major handicap. The Swiss expect high quality, fair pricing, and a strong degree of social responsibility when it comes to jobs and services in the public sector companies.

Recently, the planned CHF 0.20 hike for next day postal delivery (the first in 18 years) from January 1st has been halved following a popular and political outcry. Some service cuts have been implemented, with post office closures and the transfer of counter services to other outlets, such as local stores. But Switzerland’s particular geography, with its isolated mountain communities, has made closures particularly sensitive.

Diversification has its dangers

Even earnings boosting diversification can be tricky. Rutz recalls the failures of state telecoms group Swisscom (and, earlier, state airline Swissair) to push acquisition led growth abroad. The jury is still out on whether Swiss post’s shifts into booking software, digital advertising, secure data transfers in the cloud, and electronic identities will pay out. Some may ask, more fundamentally, whether public sector companies, enjoying significant financial privileges, should ever enter markets already covered adequately by the private sector. Switzerland’s tight postal law could also present legal obstacles to excessive diversification.

Clearly, there are no easy answers to squaring the circle of offering cost effective public services amid sharply changing consumer preferences and deregulation. A sensible preliminary step would be to examine closely the performance of similar companies elsewhere in Europe and, depending on the circumstances, mimic initiatives that have worked while avoiding the failures.

Another is to accept that, while never giving up the struggle for greater efficiency and productivity, their public service mandate prevents all such companies from behaving like true private sector counterparts. It is up to politicians, and ultimately voters, to decide how much public service they are willing to pay for.