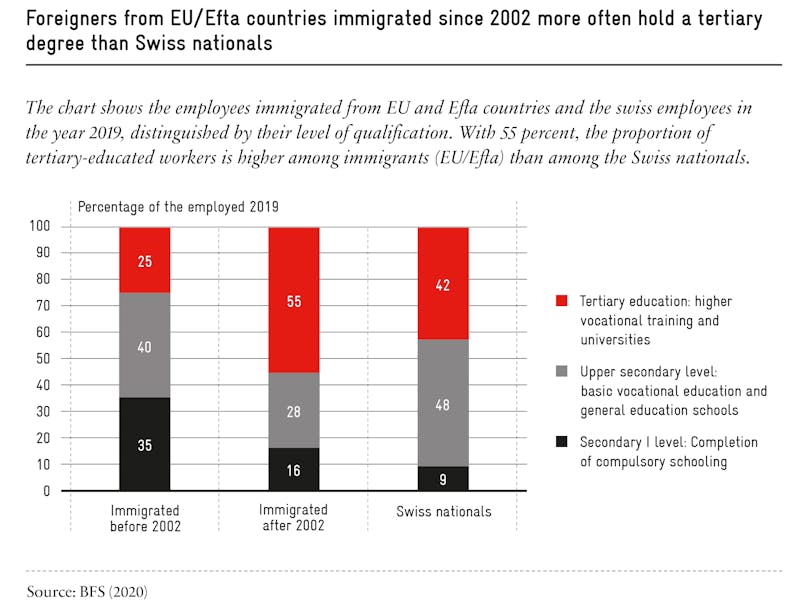

The free movement of people from the EU to Switzerland has prevented educational levels from declining thanks to the arrival of large numbers of skilled workers with tertiary education (higher vocational training and universities) (Seco 2019).

Before liberalization, Switzerland’s foreign labor pool was restricted by a rigid quota system. Immigration was determined by a few industries that depended primarily on low-skilled staff and which exerted great influence on politics. Today, most immigration is no longer politically controlled, but depends on economic demand. Swiss companies recruit the well-trained specialists they cannot find at home.

People with tertiary education account for the largest slice of immigrants on

Our chart shows employees from EU and Efta countries (excluding dual citizens) by immigration date working in Switzerland in 2019. Immigrants who left the country before 2019, were naturalized or retired earlier are not included for statistical reasons.

Of all the EU and Efta foreigners who emigrated to Switzerland since 2002 and were employed here in 2019, an average 84 percent had at least an upper secondary level, meaning basic vocational education and general education schools, such as grammar schools. Some 55 percent boasted tertiary level education. Compared to the Swiss workforce, most immigrants from the EU and Efta achieved school leaving certificates while those with tertiary education was higher.

Although immigration declined for a while after the 2014 mass immigration initiative and its uncertain implementation the composition of the qualification structure of immigrants changed little. Skilled workers with tertiary educational standards continued to account for by far the largest share. In 2018, more than half workers who had emigrated to Switzzerland under the provisions of free movement had a tertiary degree (Seco 2019).

Immigrants complement the existing qualification structure

The data show workers from the EU and Efta mainly supplement occupations with low or high qualifications, and less frequently sectors requiring medium qualification levels, thereby filling important gaps. Broadly speaking, and taking into account specialist fields such as medicine, where student numbers are deliberately limited, a “brain gain” has been taking place.

Closing the human capital gap

Switzerland benefits from free movement in several ways: it can close its labor market skills gap with foreign specialists, while not having to pay for their training. At the same time, the high proportion of highly qualified migrants evidently does not devalue local educational qualifications given that the “education premium” (the wage gap between highly and low-skilled workers) has increased between 1995 and 2014 (Weisstanner and Armingeon 2018).

A study by Favre et al. (2018) indicates the extent to which the quality of the educational qualifications of EU and Efta immigrants differs from that of their Swiss counterparts. Foreigners with tertiary qualifications who arrived since the introduction of free movement on average already earned more than Swiss nationals in the year of immigration, one reason being that a relatively large proportion of those foreigners were employed in very well-paid jobs (as managers, doctors, etc.) while immigrant women tended to have a higher workload than their Swiss counterparts (Seco 2018).

Some 57 percent of EU and Efta immigrants since 2002 came from Switzerland’s direct neighbors (Germany 28.5 percent, France 12.5 percent, Italy 12.9 percent, Austria 3 percent) and therefore spoke at least one of the national languages (BFS 2019a). Cultural or communication problems were unlikely to be problematic, as 70 percent of the population from EU and Efta countries had advanced or native language skills in one of the official languages in their canton of residence (BFS 2019).

Conclusion

Free movement has benefited the qualification structure of immigration, since it is primarily highly qualified workers who have arrived. The proportion of tertiary-educated immigrants is even greater than that of Swiss nationals. Free movement is unlikely to have a negative impact on the quality of schooling, as most EU and Efta immigrants have a tertiary degree and speak a national language.

This article was first published in “Personenfreizügigkeit – Eine ökonomische Auslegeordnung.”