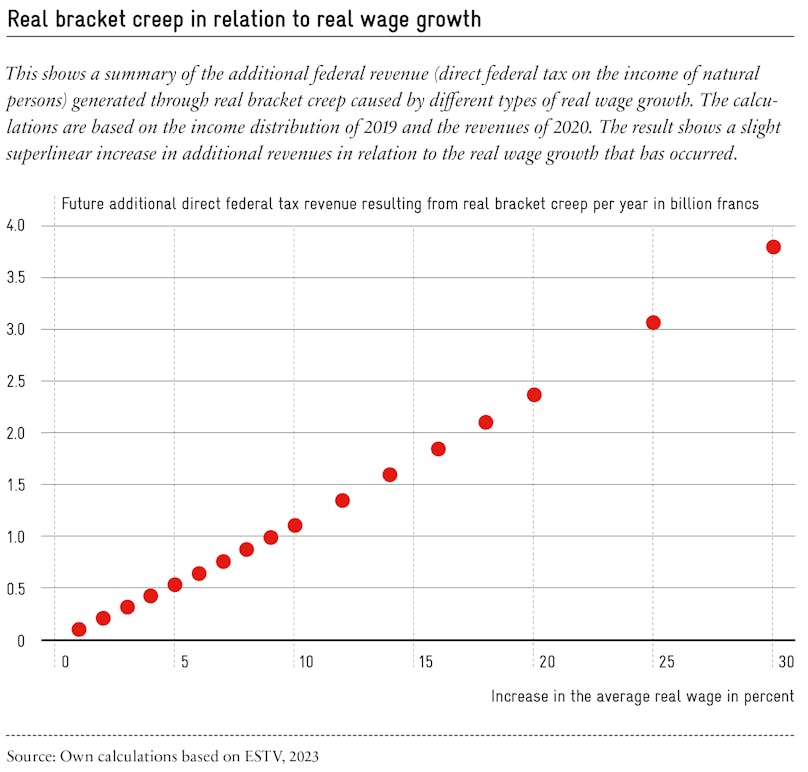

At the beginning of August, Avenir Suisse’s report on the full financial implications of so-called real bracket creep caused quite a stir ‒ and rightly so. The phenomenon and its effects are largely unknown to the general public, even though the Basel FDP politician Baschi Dürr already described (and named) it back in 2007. Real bracket creep describes the way the entire population slowly rises up the tax table as a result of real wage growth.

Any increase in income that moves a household further up in the national income distribution is accompanied by a disproportionate increase in its tax burden. This is commonly accepted, and in terms of tax fairness, it’s also what the electorate wants. After all, the whole purpose of a progressive tax system is that those who earn more should contribute a higher share of their income to the funding of public services.

A household with an increasing income that remains, for example, in the middle of the income distribution is over time burdened with an ever-higher tax rate. This can’t be objectively justified; nor is it intended to be so. This real bracket creep leads to an insidious increase in the fiscal quota over time and undermines efforts to limit the government footprint, for example.

But there’s more: ironically, real bracket creep weakens the progressivity of the tax system. Because more and more households are moving up to the highest tax brackets, the share that really rich households contribute to the total tax volume is decreasing. This leaves the middle class primarily bearing the resulting costs. Because of real bracket creep, the tax system is increasingly failing to fulfill its socio-political function: redistribution from rich to poor.

But if these unintended effects of real bracket creep are so obvious, why are they not being compensated ‒ just like “normal” bracket creep?

Here are six poor arguments for not compensating for real bracket creep.

A manual adjustment is possible at any time

In a report to the Federal Council in 2017, it was suggestively asked why “mistrust in future political processes is so high” that an automatic mechanism for correcting real bracket creep was considered necessary. A tax cut could be brought about by an initiative at any time. Systematic compensation of real bracket creep, according to the report, was thus unnecessary.

This argument is as cynical as it is out of touch with reality. Collecting signatures and fighting referendums involves substantial costs. Moreover, a referendum campaign for a general tax cut is unlikely to address the real bracket creep phenomenon. And in general, the statement negates the normative power of the status quo.

Real bracket creep has been offset by other tax benefits

Counterarguments often claim that real bracket creep has been compensated to a considerable extent by an increase in tax deductions in the past decades. The Federal Tax Administration calculates that in 2015 ‒ based on real wage growth over the past 20 years ‒ real bracket creep “only” generated additional revenue of around CHF 450 million for the federal government. Those estimates, however, already offset any changes in tax deductions (married couples’ deduction, child credit, childcare deduction, cap on second-earner deduction).

Tax deductions are democratically legitimized and always relate to a specific concern in the political debate, be it marital status, childcare or the division of labor in the household. Increased deductions are thus no compensation for “real bracket creep,” neither in the respective debate nor as a systematic approach. The fact that real bracket creep has been partially compensated by an increase in tax deductions therefore does not hold up as an argument for not compensating for it.

Compensating for real bracket creep restricts the scope for fiscal policy

The Federal Council’s negative response to a motion submitted by FDP Council of States member Andrea Caroni in 2019 on compensating for real bracket creep is telling. The Federal Council mostly quotes from its report on the fulfillment of an interpellation in 2014. At first glance, the quotes seem off-topic and out of place. At second glance, however, they turn out to be a prime textbook example of political economy manifested in the here and now.

The Federal Council writes:

Furthermore, automatic compensation of real progression would preserve the existing tax system or existing expenses. The reason for this is that there is less fiscal policy leeway for changes to the tax system or the tasks of the state if real progression is equalized. When implementing tax reforms, for example, greater care would have to be taken to ensure revenue neutrality. This, in turn, increases the number of losing parties in a reform and consequently the likelihood that the reform will fail in the political process. As a consequence, the automatic elimination of real progression would limit the possibilities to adapt to changing social conditions.

Compensation for the real bracket creep reduces the possibilities for changes to the tax system or the tasks of the state. What exactly does the Federal Council mean by this?

Changes to the tax system so far have almost always been implemented through new deductions (such as those already mentioned or, for example, commuter deductions, etc.). But such deductions don’t come for free. Either the money must be saved somewhere else or the state finances deductions by raising taxes elsewhere. It turns out that precisely the latter happens with real bracket creep! Without the public noticing, the state has pre-financed new deductions, so to speak. Politicians can take credit for tax cuts benefiting a specific target group without the population realizing that this has ultimately come at the cost of a general tax increase for everyone. In fact, the Federal Council is right in saying that compensating the real bracket creep “limits the possibilities for changes to the tax system.” Without the “free” tax money from real bracket creep, it would become much clearer that potential tax measures have losers as well as winners. Using this effect as an argument against compensating for the real bracket creep, however, seems somewhat blatant.

The same applies to the “changes in the tasks of the state” (here “changes” is a euphemism for “expansion”). The additional revenue from real bracket creep makes it more affordable for the state to take on additional tasks. After all, they are pre-financed by taxpayers, and above all by the middle class. Only they know very little about it. For a country that prides itself on its strong direct democracy and fiscal equivalence, this is hardly flattering.

Another three poor arguments

In the same statement on the rejection of the motion, the second important feature of real bracket creep, its degressive effect, is not even mentioned. As explained earlier, real bracket creep actually lowers the relative redistribution from rich to poor.

Furthermore, it is pointed out that the debt brake, among other things, already helps prevent the expansion of state activity. But real bracket creep actually undermines this effect. The federal and cantonal debt brakes do prevent a systematic increase in government debt, but they do not prevent the fiscal quota from rising automatically with increasing prosperity.

And last but not least, the Federal Council warns of significant tax losses for Switzerland caused by the upcoming OECD tax reform. It concludes that “Given this context, tax reforms that do not have a relevant effect and in terms of business development in which the revenue base will be eroded do not appear opportune at present.” This statement is wrong on two counts: First, the implementation of the OECD tax reform (minimum tax rate of 15% for large international companies) is expected to generate additional revenues, not fewer. Second, compensating for real bracket creep does not lead to an erosion of the tax base, but merely prevents its continuous, disproportionate expansion, which is hardly legitimized by direct democracy.

The politico-economic logic of real bracket creep

So politicians and public administrators benefit from the leeway created by real bracket creep at taxpayers’ expense. Because it accumulates in a creeping process over the years, it is hardly noticed, let alone reported explicitly. It can therefore be regarded as a kind of tax illusion. While people are aware of the current size of the tax burden, there is a lack of awareness that the tax burden increases continuously over time and that government revenues rise accordingly. This creates political capital: Politicians can score points with tax cuts that have become possible merely because of real bracket creep resulting from real wage growth ‒ not because of a restrictive fiscal policy or good governance.

It is hardly surprising that politicians and administrators have so far shown little interest in automatically compensating for real bracket creep ‒ or even in creating transparency about the phenomenon. All the more reason why it’s about time to change this state of affairs!

For more information, see our report on real bracket creep.