Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine more than a year ago, almost 10,000 civilians have been killed, most of them by air strikes on civilian infrastructures. This has been a wake-up call for other European countries, none of which could currently provide sufficient protection for its population or critical civil and military infrastructure. For this reason, Germany launched the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) in 2022 which eighteen other European countries have joined since. The initiative primarily revolves around the procurement of market-available ground-based air defense systems. Last July, Switzerland’s declaration of intent to join the project triggered political criticism in the country.

Protected by the shield …

The ESSI was created because the threat from Russia was expected to continue, and it is likely that Russia will restore its missile arsenal in the medium to long term. Although Russia would be inferior to NATO in a conventional conflict, such capabilities contribute to its blackmail potential also below the threshold of war. The term “Sky Shield” is primarily used for marketing purposes and may evoke overly optimistic associations. It is hardly possible to defend a territory the same way the “Protego” shield spell does in Harry Potter. However, the fact that several neighboring states are joining forces adds to the project’s effectiveness.

A more realistic goal is the joint procurement of expensive systems to achieve favorable prices through economies of scale. Additionally, high costs incur for training and maintenance, where synergy effects are thus to be exploited. Finally, the aim of the initiative is also to reduce Europe’s air defense dependence on the USA.

… or in the rain?

Even if the idea is interesting from an economic point of view, a glance at the map shows that the ESSI is not met with the same response from all NATO and EU members. Given industrial policy interests, committing to certain systems could lead to political tensions with states that are procuring or have already procured other air defense solutions. While the ESSI relies on the U.S. Patriot system for large interception ranges (up to 100 km), France and Italy rely on the European SAMP/T. On the other hand, Poland, currently strengthening its defense policy, directly procures Patriot and does not rely on Germany’s IRIS-T SLM, which is intended for the ESSI, for medium ranges (up to 35 km).

Furthermore, numerous strategic and tactical questions emerge. Ultimately, the question is how to integrate the ESSI as a political initiative into NATO’s existing air defense structures. To avoid escalation, NATO’s missile defense system was explicitly targeted at threats from outside the Euro-Atlantic area (e.g., Iran) and not at Russia. It should be noted that the acquisition of Arrow-3 (with ranges of over 100 km) has not been included in NATO’s defense plans so far. It also remains to be seen whether the initiative’s potential can be fully exploited without Poland, with its geographically important location.

An opportunity for Switzerland?

Joining the ESSI may have come somewhat as a surprise, but a closer look reveals some considerable potential, as Switzerland too has major weaknesses in its air defense. Aware of this, Switzerland opted for the American Patriot system last year as well, meaning that it could benefit from the ESSI’s acquisition of ammunition. However, since the Patriot is only suitable for long-range defense, Switzerland is likely to procure a short- and medium-range defense system as well. If the German IRIS-T SLM chosen by the ESSI is suitable, it could probably be bought at a lower price through the initiative.

Critics suspect that Swiss participation in the ESSI would pose problems for the neutrality policy. As it is not yet clear exactly in which direction the initiative will go, Switzerland should closely follow the above-mentioned developments regarding integration into existing structures. However, this participation is not a step towards NATO membership. The declaration of intent, which was signed together with Austria (also a neutral country) assures Switzerland that it can withdraw in the event of a conflict involving another ESSI member.

A fully autonomous air defense system would be fundamentally difficult for Switzerland to manage. In the event of a possible air attack, not only Switzerland but at least its neighboring countries would be affected as well, and Switzerland would have to protect its airspace with those states. Joining the ESSI means being aware of this and represents a sensible and pragmatic approach to neutrality. At the same time, Switzerland can test to what extent increased cooperation on security policy with NATO and the EU could work.

Safety comes at a cost

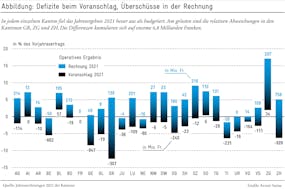

What is clear already today is that strengthening the defense capability of its military system will cost Switzerland dearly. According to the army, CHF 13 billion will be needed between 2024 and 2031 for armaments procurement alone. The army budget will be increased accordingly by 2030. Particularly in times of a tight federal budget, the army is obliged to procure its material as cost-efficiently as possible. International cooperative ventures such as the ESSI are therefore an ideal solution.

As long as Switzerland does not exhaust every option, any measures such as a temporary waiver of the debt brake for armaments procurement, as put forward this summer in a motion in the Council of States, are unacceptable. Of course, the army should still procure the most competitive systems, whether they are part of the ESSI or not. Participation in the initiative does not restrict the freedom of decision in this respect. The ESSI is therefore a good opportunity to send out a signal of willingness to cooperate, especially to European partners, at a time when Switzerland is once again under increasing international pressure.