Switzerland’s sanctions on the Russian aggressor have triggered an illusory debate on neutrality. The fact that some commentators see the mere act of going along with economic sanctions as a threat to neutrality testifies to a highly mythologized understanding of the term, an understanding that doesn’t hold up to the historical realities. Former Swiss ambassador Daniel Woker, by contrast, believes that Switzerland would have acted against its neutrality had it not adopted the sanctions.

Joint Defense

As a study on security policy published by Avenir Suisse in late March reveals, calls for Switzerland to engage in closer transnational military cooperation raise genuine questions about neutrality.

As people at the Federal Department of Defense, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) are at pains to point out, Switzerland is already cooperating transnationally and has intentions to expand. However, cooperation with NATO (despite being more significant than cooperation with the EU) accounts for less than 1 percent of Swiss personnel and defense spending. DDPS officials oppose joint defense exercises with NATO troops or participation in EU battlegroups. But where exactly does the contradiction with neutrality lie?

A territorial attack directed exclusively at Switzerland is still hard to imagine. Should Switzerland have to defend its territory nevertheless, we would probably have to rely on assistance from surrounding countries.

Designed for joint defense: The new F-35 fighter jet during testing in Emmen. (Orlando Bassi, Unsplash)

The F-35 fighter is also geared to joint defense. Under the 1907 Hague Convention, a neutral state has the duty to assure its defense. If threat scenarios make a joint response seem likely, it’s only logical to train these capabilities. The fact that this is possible even without a formal declaration of assistance is demonstrated by the two (so far) neutral or non-aligned states Sweden and Finland.

Sweden participates in the NATO Response Force (NRF). The country has also signed a memorandum of understanding which enables logistical support for allied forces located on or crossing its territory, during exercises or in the event of a crisis.

The Nordic defense declaration Nordefco (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden), as well as various bilateral and regional defense cooperations, including NATO cooperation, manage to harness the potential of Sweden’s neutrality (i.e. non-alignment) without formal declarations of assistance. Sweden’s defense strategy is thus geared to transnational cooperation. The Swedish Defense Agency, for example, writes in a study (published before the Ukraine war) that especially in the new multipolar environment of asymmetric threats and global terrorism, defense policy automatically has an international dimension and requires transnational solutions.

After the end of the Cold War, Finland continued to develop its understanding of neutrality on the basis of a reassessment of the threat situation. Since then it has talked only in terms of non-alignment ‒ even though Finland continues to be recognized as a neutral state under international law.

There is extensive defense cooperation between Finland and Sweden, including bilateral deployment planning. Finland is likewise part of Nordefco, which aims to increase interoperability and create legal and political foundations to be able to move military units and equipment across borders.

Furthermore, Finland is an active NATO partner. Fundamental areas of the Finnish armed forces, such as naval and air force units, are trained to meet NATO interoperability standards. The relationship with NATO is further strengthened through bilateral cooperation with the US and trilateral agreements with the US. and Sweden. In total, Finland participates in around 70 international military (NATO) exercises each year. The country also participates in NATO missions, for example in Iraq.

Great Potential for Switzerland

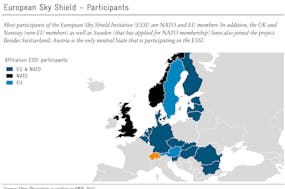

In response to the Russian threat, Finland and probably also Sweden striving to join NATO in the near future. This would entail giving up their neutrality under international law. This is not an option for Switzerland.

Nevertheless, the transnational cooperation between the two Nordic countries shows how much potential there still is for Switzerland ‒ even if it complies with its (self-imposed) duty of neutrality ‒ in defense cooperation. The extent to which it wants to exploit this potential should be discussed taking pragmatic account of the geopolitical realities. This would be a worthwhile debate on Swiss neutrality ‒ not a sham debate on participation in sanctions on a unilateral aggressor.